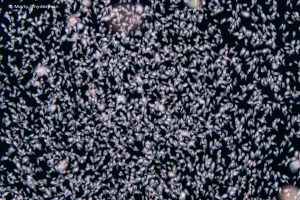

If asked to name the greatest migration on Earth, many people would surely say the annual journey taken by caribou. Others would likely list the treks taken by wildebeest or Arctic terns. Certainly, these migrations are noteworthy in terms of the distances traveled. But in terms of biomass and the number of animals involved, the greatest migration on Earth happens in the world’s oceans. In a phenomenon known as diel vertical migration, trillions of tiny marine animals ascend from the depths at night to feed only to descend to avoid predators as the Earth rotates and daylight approaches. Traveling from as deep as 3,000 feet, an estimated 10 billion tons of zooplankton make this daily sojourn to feed on phytoplankton that is abundant in surface water. In turn, the zooplankton attract an array of predators that range from larval and post-larval fishes, salps, krill, jellies, comb jellies, copepods, worms, and shrimps to octopuses, squids, and other mollusks.

In recent years, the allure of photographing the creatures that are involved in this nightly event has become increasingly popular. Known as blackwater diving, the opportunity to try one’s hand at photographing the creatures of the open ocean after sunset is now available in an ever-growing number of destinations around the globe.

Typical blackwater dives go something like the following: Photographers set up a camera system with a macro lens. They also make sure they have a working primary dive light and several backup lights to go along with their pressure and depth gages. A thorough dive briefing is provided before participating divers head to sea on a boat ride that can be as short as a few minutes to considerably longer depending on the bottom topography, selected diving location, and prevailing conditions.

Once the boat is on location, the crew will deploy a brightly lit surface buoy and an array of submerged lights that are attached to the buoy via a weighted downline. The lights essentially serve as the bait. Unless a sea anchor (usually a parachute) is used to slow the boat’s drift, the surface buoy will not be tied to the boat as wind might cause the boat to move too fast for the divers to keep pace. The divers wait 30 minutes or so before entering the water to give the lights a chance to attract creatures of the night.

Once the divers are in the water, a boat that is not using a sea anchor will move away from the buoy and the divers while the captain and crew keep their eyes the buoy. The boat will be equipped with bright lights that surfacing divers can easily see. Upon surfacing, the diver will use one of their dive lights to signal the boat for a pickup.

In scenarios in which a sea anchor is deployed, the boat’s lights serve the same purpose as a lit surface buoy and the weighted downline of lights is attached to the boat. In these scenarios, the boat remains directly above the divers throughout the dive.

Lights on the downline are attached at intervals of 10 to 15 feet to a depth of around 60 feet. Some divers will go slightly deeper than the deepest light, but many blackwater divers, especially those who are newer to the blackwater experience, choose not to. Keeping their eyes on the lights and never venturing beyond a range in which the lights are easily visible, photographers and dive guides look for potential photographic subjects while drifting with the lighting array.

In my experience when a surface buoy is used, divers are instructed to surface close to the buoy and to swim away from the buoy once the boat is coming to pick them up. During the “pickup”, the diver shines their light as instructed during the dive briefing so the captain and crew can see the diver, but the diver is instructed not to shine a light directly at the boat or into the driver’s eyes.

What the Diving is Like

“Is blackwater diving scary?” This is a question new blackwater divers almost always want answered. In my experience, everyone, no matter how experienced they are as a diver, has some angst about being in the open sea at night. But almost every diver goes from that “heart in their throat” feeling to surprisingly relaxed within a matter of minutes once they are underwater. The setting often looks and feels like being in a well-lit swimming pool that happens to be very deep.

Monitoring depth and staying close to the surface buoy and downline throughout a dive is usually easy as the glow of the lights make a great reference. Even if there is some current, the lighting array and divers tend to move in the same direction at the same speed. So, while you might drift several miles during a single dive, in the water you do not feel or have to “fight” any current or movement. Just keep the lights on the downline within view and you will not drift away from where you want to be.

“What about sharks?” This is another commonly asked question and somewhat of an elephant in the room. The truth is, there are a variety of sharks, including the silky shark pictured here, that roam the open sea. Depending on the location and the given night, sometimes sharks come in to take a look around. But, just like diving during the day, it is usually people’s imaginations that cause any issues.

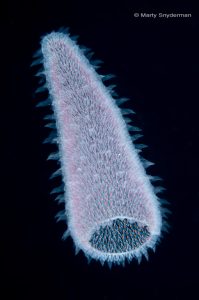

While you never know what animals might be encountered on a given night, some commonly encountered creatures include larval jacks, filefishes, seahorses, moray eels, octopuses, mantis shrimps, sea jellies with accompanying fishes, shrimps and crabs, comb jellies, larval lobsters, chambered nautiluses, pyrosomes, squids, octopuses, and more.

Occasionally, divers find themselves in pockets of water where there is very little life. But that is the exception, not the rule.

Some larval creatures look like miniature adults, while others are bizarre looking and seem to bear little, if any, resemblance to their parents. Trying to figure out “who is who” is part of the challenge and thrill of blackwater diving.

If fate is kind, some of the encountered creatures will eventually settle to a reef that is shallow enough for sport divers to explore. Others remain in the water column throughout their lives. If fate is not kind, still others will soon be someone else’s meal.

How To Find Good Subjects and How to Photograph Them

A problem photographers routinely encounter is that a continuously burning dive or video light often attracts clouds of small crustaceans, worms, and other invertebrates that end up as ruinous backscatter in photographs. The technique employed by many experienced blackwater divers to combat this issue is using a very bright light that has a narrow beam to find and approach subjects while mounting a focusing light on top of their camera. A short lanyard is used to attach the bright light to one of the photographer’s wrists. Because most shutter release mechanisms are on the right side of cameras and housings, the bright light is usually held in the diver’s left hand and attached to the diver’s left wrist. The focusing light on the camera is not turned on until the photographer is ready to try to compose and capture an image.

Sometimes planktonic creatures gather around the bright light in the photographer’s hand. But when the photographer gets close to a subject, the photographer lets go of the light. The light will drop straight down and dangle below the photographer’s hand. Being attached to the diver’s wrist, this light will not be lost to the depths, but it will cause most of the planktonic life forms to swim downward to stay in the light’s beam.

Just before letting go of the bright light, the photographer turns on their focusing light. Because it was not turned on earlier, the focusing light will not have attracted any planktonic life forms. This allows for a relatively clean frame when the photographer begins to compose a photograph. Depending on the night and a variety of factors, the focusing light might eventually attract planktonic creatures that lead to backscatter. So, being quick to compose and shoot is sometimes necessary.

Focusing on and properly exposing subjects can be tricky. No matter how experienced a blackwater photographer is and what camera and lighting system are being used, the shooter is likely to suffer some frustration and photographic failure. Depending upon a photographer’s angle of orientation, many subjects like this squirrelfish are highly reflective.

This can make focusing anywhere from suddenly very hard to impossible. You just have to keep trying to find an angle that can produce a pleasing frame and allows the camera system to acquire focus.

It is also challenging to keep subjects in a frame as the field of view of a macro lens is rather narrow and many subjects such as this post-larval trunkfish are active swimmers.

Even if subjects remain still, it can be quite a challenge to find and keep a subject in a viewfinder, much less compose a pleasing frame.

Obviously, if a subject is actively moving as was the case when I photographed this flatfish:

And this larval crab:

Framing and focusing become even more challenging. Once again, persistence can be a key to success.

The best focusing option to use is camera, lens, and subject dependent. If you are having trouble acquiring focus, it is often wise to change to another focusing option. For example, you might find that using the option to focus on the eye of an animal is not working well, so you will need to use more focus points and focus on the edge of a subject where the subject and water intersect. In some instances, continuous focus works well, but in others this option is not a good choice. The bottom line here is, know your way around your camera system by feel so you can quickly change from one focusing mode to another in the dark because you are likely to want to do so on many blackwater dives.

Acquiring proper exposures is another tricky part of blackwater photography. Many potential subjects, especially gelatinous creatures, are translucent and light from a strobe seems to pass right through them without being reflected to the camera’s sensor.

The same is true of some larval fishes. So, wide open apertures that gather as much light as possible become necessary to attain proper exposures. Of course, a wide aperture with a macro lens results in a thin depth-of-field. Conversely, highly reflective subjects- and there are plenty of those- necessitate closed-down apertures and changing the angle of orientation to get the desired image. Bracketing exposures, reviewing results, making the necessary adjustments before moving on to look for another subject, and shooting a lot of frames of the same subject are often keys to creating a photograph that pleases you.

No doubt about it, the ratio of great shots, even just keepers, to disappointing results is lower in blackwater photography than it is in many forms of underwater photography. While the learning curve can be steep, there is no doubt that photographic successes from blackwater dives are especially rewarding. So, remember to enjoy the process, not just your processed images when you photograph the marine animals that take part in the greatest migration on Earth.