Shoot Stories text and photography by: Marty Snyderman

When first trying their hand at underwater photography, many divers feel a sense of accomplishment if their photography equipment is dry where it is supposed to be and functioning properly after their dives. Soon, that feeling of achievement requires making pleasing pictures of the scenes and animals they photograph like this shot of a California sea lion pup giving my camera system and me a once-over.

Many photographers are quick to share those images with family and friends with some of these photographs garnering a lot of “likes” and even “WOWS!” on social media sites. But if you reach this level of achievement, don’t let it be the end of your photographic road.

One way to take your work to the next level is to challenge yourself to capture a series of images that tell a story about an animal, dive, trip, destination etc. Having a story in mind will help you envision the specific scenes, animals, behaviors etc. you want to capture to tell your story. With your photographic thinking being more sharply focused, you are highly likely to be able to streamline your efforts underwater when time is critical.

Writers and photographers who worked in the days when printed magazines, books, newspapers, guides etc. were printed faced the dilemma posed by having limited space for the images that got printed. Editors had a limited number of pages and space to dedicate to any given story and their guidelines were usually set in stone. When a photographer claimed to need more space or to print more images, the response from editors was almost guaranteed to be something like “you need to tighten up your story” or “go back and make images that allow you to tell your story with fewer photographs”.

Today with the increasing number of online publications, space is not as limited in many situations. However, people’s attention spans are. So, the same advice from the editors of printed publications still has a lot of merit. Study after study about online publications reveal that readers don’t finish articles at anywhere near the same rate as when pieces appeared in print. While space might not be limited, human nature limits how much time people will spend reading or looking at any given story in an online publication. In short, the photographic adage remains true. Less is often more when it comes to telling a story with photographs.

Another reason to try to “shoot stories” is that this goal gives you good reasons to go back to the same dive sites and photograph the same animals or scenes again and again until you get the shots that tell the story you want to share.

Let’s look at some examples.

Here are eight images I made on a recent trip to the Atlantis Dive Resort in Dumaguete, Philippines. While this collection of images represents some of the variety of subjects and scenes I enjoyed and some images that would probably be “liked” on social media, there is no theme-based story to share. In essence, these images can accurately be described as a collection of pretty pictures.

a flagfin shrimpgoby watching for potential predators while its partner shrimp maintains their shared burrow

a porcelain crab with a clutch of eggs

the face of a tassled scorpionfish

the face of a tassled scorpionfish

a whale shark feeding on krill provided by fishermen at Oslob

a pair of white-eyed morays peering out of their shared crevice

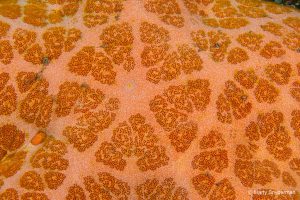

close-up of the skin of a granular sea star

close-up of the skin of a granular sea star

a linecheeeked wrasse being cleaned by a bluestreak cleaner wrasse

a green turtle resting on the sea floor at Apo Island

In my opinion, both of the following two collections are far more compelling. The first one is a story about reproduction in pink anemonefishes. The images I chose to share show where a diver is likely to find a pink anemonefish,

where a female pink anemonefish lays her eggs,

how she protects the eggs by guarding them,

and how she keeps the eggs free of debris.

To further flesh out my story, I would love to have the opportunity to photograph a diver looking at pink anemonefish to provide perspective regarding the size of these damselfish, courtship, mating, a female depositing her eggs, and hatching. This “want list” will help me have specific goals on future dives. Wish me luck!

The following eleven images comprise another story about courtship, mating, eggs, and hatching that divers might see in different locations. The story is about sex on the reef and features a variety of creatures as opposed to focusing on a single species.

In this photograph, a male Bartlett’s anthias is displaying in an effort to woo a female.

Here you see a pair of mating mandarinfish, an event that follows courtship. These spectacular fish are found in rubble zones throughout the Indo-Pacific. They court and mate on many evenings right around sunset.

Mating nudibranchs reveal a different aspect of the reproduction story. Nudibranchs are simultaneous hermaphrodites, meaning each mature individual has functioning male and female sexual organs at the same time. When nudibranchs mate, it really is a case of boy meets girl meets boy meets girl! In nudibranchs, their sexual organs are located on the right side of their body. So, when mating, the two animals are side by side while facing opposite directions.

This photograph shows a nudibranch laying its already fertilized eggs in an egg ribbon.

In a variety of reef fishes, males protect the fertilized eggs of their mates by “gluing” the eggs to their body, holding them in a brood pouch, or holding them in their mouth until the eggs hatch. These males are sometimes collectively referred to as “Mr. Moms”, a reference to the fact that in Nature it is usually the female that protects the eggs in species in which some parental care is involved. This photograph is a shot of a male banded pipefish with a clutch of eggs “glued” to his belly.

This photograph shows a male yellow-barred jawfish protecting the fertilized eggs of his mate by holding them in his mouth, where the eggs will remain for approximately five to seven days until they hatch.

Here you see a baby California horn shark hatching. Many sharks bear live young, while some, like this California horn shark, lay eggs.

Female sea turtles lay their eggs in nests they dig on sandy beaches in tropical and sub-tropical areas. Upon hatching, young turtles quickly make their way to the water …

and then out to sea.

Clearly, this is not the entire story of reproduction in the sea, but there are enough images to create an interesting piece that shows that that there is more than one way that marine animals reproduce and to peak viewer interest about this topic.

I have the ability to share these and more images in Sources. But that is not the case with some other publications that more strictly limit the number of words and images.

My takeaway message is to encourage you to challenge yourself to shoot a specific story instead of swimming around and photographing any scene and animal you see. Shooting stories will elevate your photographic thinking and help you take your work to the next level.

Along the way, remember to enjoy the entire process, not just your processed images!