Neighbors, who know that I dive off Boynton Beach often ask me, “How’s the ocean look below?” It is an easy enough question to answer — if I fend it off as I would the more usual, “How are you doing?” “Good” is my usual answer. Very few have the interest to listen to more. It is a polite conversation: a quick hello and a polite question.

But if it were not for the Gulf Stream, South Florida would be a noisome sewage sump. No one could have predicted the population surge in Florida. Not that long ago, everything west of Military Trail in Boynton Beach was either swamp or orange groves. My uncle urged me to buy five acres of land west of Military Trail. It was selling for $1,500 an acre. I retorted that it was just swamp. That swamp has been filled in, and a gigantic shopping mall has been built over it.

What about the Atlantic Ocean? It just keeps coursing along. Occasionally beaches are closed because of sewage spills and pollution. That is tolerable to most residents, but it’s a disaster to tourists who paid for a week in the sun. Florida is now the third most populous state in the U.S., and all these folks have needs. They have amusements and pastimes. They have animals and major agricultural pursuits that support them. All this generates waste, runoff, and disaster.

No drop of water simply disappears. Whatever is spilled on the land, whether gasoline, insecticide or animal urine doesn’t just go away. Besides toxic chemicals that do not degrade, the ordinary waste contains high levels of nitrogen. Fertilizers used on golf courses and lawns, herbicides and pesticides, everything that human occupation of the land finds necessary to maintain a level of the lawn and recreational living either evaporates, eventually coming back down in the rain, or it just sits there until it washes off with the rain. Storm drains carry the wastewater to canals or directly into the Intracoastal Waterway then, at tide change, into the Atlantic Ocean.

Clearly, I could not get that mouthful out to anyone who simply sought a polite answer to their cursory question: “How’s the ocean look below?”

Algae are killing the coral. Coral is the substrate that supports life on Florida’s reefs. Directly offshore from Boynton Beach, about a mile off the beach is one of Florida’s most beautiful reefs. The reef runs north and south in a regular pattern. It is about 450 meters (500 yards) wide, narrower or wider in some spots. On the beachside, it is about 18 meters (60 feet) to the sand. The reef rises up in ledges some 3 meters (10 feet) in places. The ocean side of the reef is about 24 meters (80 feet) to the sand. There are magnificent fingers of a reef that jut out toward the ocean. Between these fingers, some niches shelter marine life. Life on these reefs is bountiful and productive. They are in grave danger.

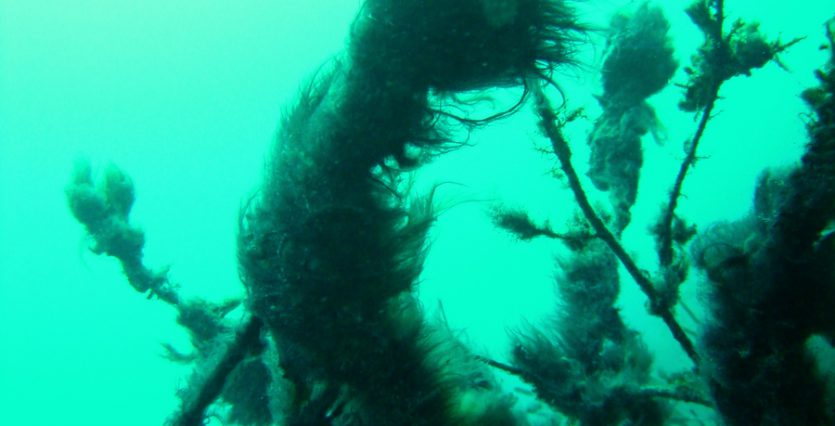

Over the years, I have watched algae take over large segments of this and other reefs along our coast. I have taken samples of the algae and studied it. I have shared samples with scientists who specialize in marine algae. The primary component is Lyngbya sp., a genus of cyanobacteria (which used to be called blue-green algae). The red algae in the cocktail is Ceramium sp.

Mats of these algae drape over soft and hard coral underwater. Not only does the algae rob the coral of sunlight, more importantly, but photosynthesis by the algae also releases sugar, which fuels the growth of bacteria on the coral. The bacteria cut off the coral’s supply of oxygen, and the coral suffocates to death.

These encrusting or turf algae are not like the coral’s symbiotic zooxanthellae, tiny algae that live in the coral tissue and use the sun’s energy to produce glucose and other nutrients for the coral. Just the opposite, they’re coral killers.

Today, vast areas of the reefs off Boynton Beach and surrounding areas have been killed by suffocating algae.

Algae love nitrogen. Nitrogen in the presence of phosphorus in seawater is a prime nutrient for the algae. These nutrients come from agricultural runoff, human and animal waste and even treated sewage that does not remove nitrogen. High-nitrogen wastes, including ammonia, flow directly from storm drains and end up in the ocean. Chemicals absorbed in the air through evaporation return to the ocean in rainfall. Nitrogen that runs off agricultural lands and treated lawns adds to the enrichment. Nitrogen-rich waters promote algal growth.

What do we do about it? Very little. Some communities have studied means by which nitrogen can be removed from wastewater. Some even implement costly systems to stem the flow of nitrogen into the wastewater stream. Laws and court battles have forced the closing of mile-long sewage pipes that dumped treated and untreated sewage directly into the Atlantic Ocean.

In the end, there are just too many people and too much grass. In Florida, our grass lawns are often only a small layer of topsoil on top of the sand. How do you keep it alive? Every so often the fertilizer truck dumps pellets or sprays nitrogen-containing chemicals as well as insecticides on it. Then it rains.

Gigantic canals crisscross Florida and move water to the ocean. The one that crosses U.S. Highway 1 in Boynton Beach has gigantic gates at the Intracoastal Waterway, which can be opened to release the flow of canal water. The high-nitrogen-content water is washed out through the inlet at tide change and contaminates the ocean.

Hurricane-force winds create rough seas that can remove the encrusting algae like a huge broom sweeping the reef clear. It has happened before, and Hurricane Irma has probably cleaned the reef again. The algae is swept away by the Gulf Stream, but the coral is still dead where the algae suffocated it, and the algae will always come back to haunt our reefs if nitrogen elimination systems are not put in place.

So how’s the ocean look below? Great, but it is in peril. Our most important living reefs, some of the world’s most magnificent ocean ecosystems, are in danger of being suffocated by marine algae given an advantage by our human population explosion.